AUTHOR: Steven Anbro

Virtual reality has enormous potential for both current and future research applications in science and medicine. The social sciences in particular stand to benefit from using virtual reality technology to conduct more accurate research, better measure specific phenomena, and collect valid, reportable data—all common challenges in various disciplines in the field. We in the Behavior Analysis Program at the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) put the technology to the test in a recent study. Read on for a look at our challenges, our simulation, and our findings.

Effectively Tackling Medical Errors and Miscommunication

In recent years, medical errors—primarily errors attributed to miscommunication among medical teams—have received increased attention. The call for specific research into them is ever-present. One proposed solution to communication errors among medical teams is to begin training medical and nursing students together, rather than separately.

Through our graduate program’s ongoing partnership with the UNR School of Medicine and the Orvis School of Nursing, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to help orchestrate interprofessional trainings for these future medical providers. As psychologists, we are always asking ourselves, “Is this training/intervention/procedure/etc. effective?” By taking advantage of virtual reality technology in pre- and post-training assessments, we can begin to answer that question.

The Simulation

Using an Insta360 Pro camera, we filmed a short 360° video simulation where a simulated pregnant mother (a fully-functional “SimMom” birthing mannequin) is having an unexpected complication: a pre-eclamptic seizure. Her doctor and nurse then work together to address the complication, while also directly addressing the viewer.

Figure 1. The simulation used in the current study.

The students viewing this simulation played the role of a “recorder” – someone tasked with confirming and repeating back critical information (medications used; dosage). This simulation was filmed with a number of opportunities for recorders to respond, out loud, to what they saw and heard.

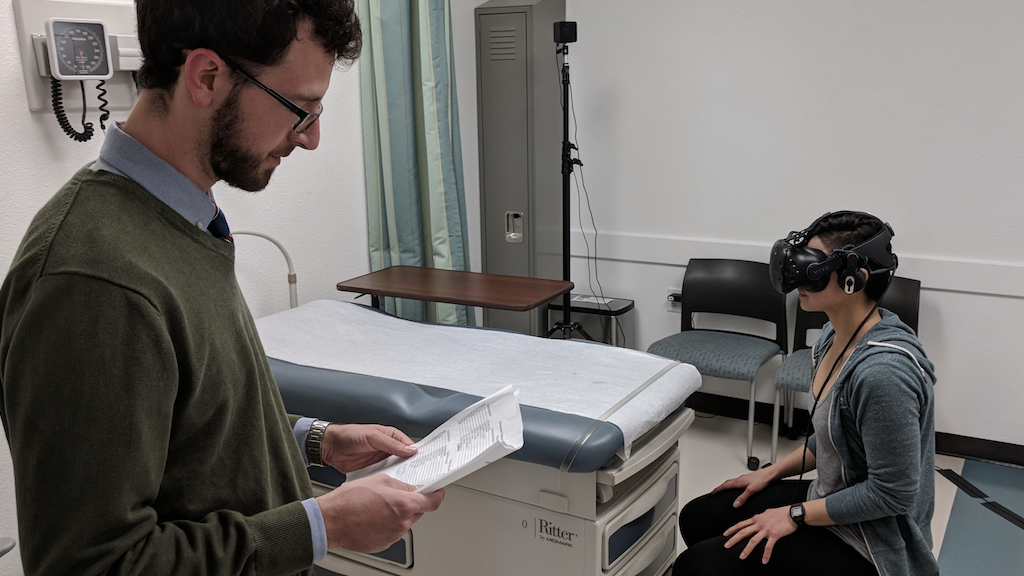

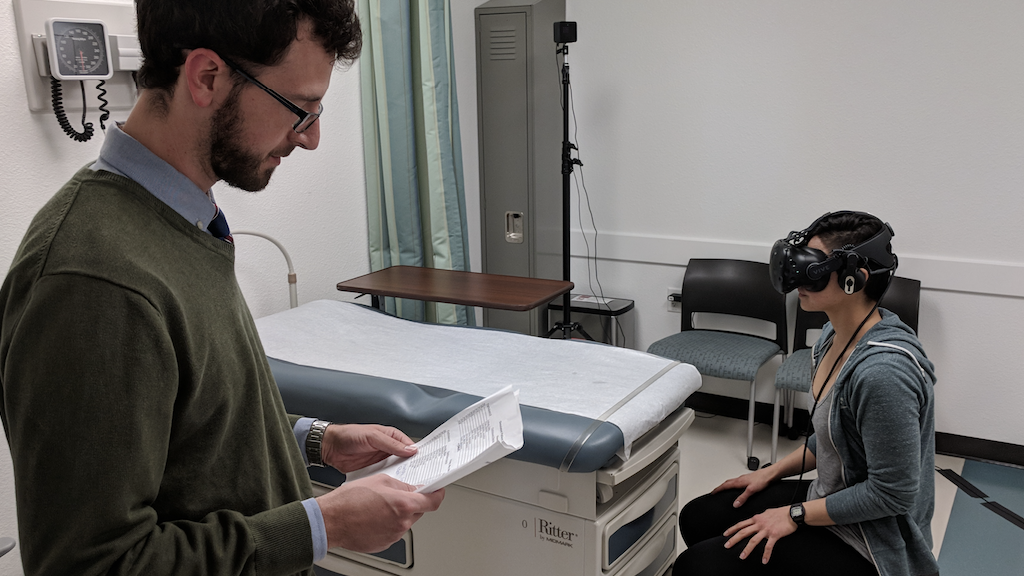

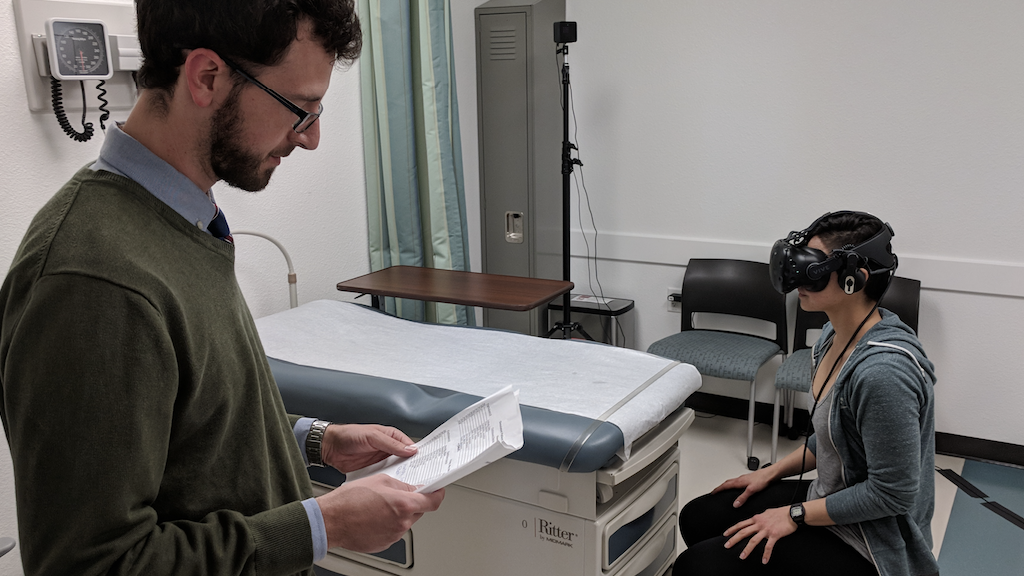

Figure 2. A research assistant orients a medical student to what they are seeing in the VIVE headset.

We had over 100 medical and nursing students view this simulation through VIVE prior to any training as a “pre-test”. We measured how often they responded to the simulation and whether their responses were correct, contained any errors or missing pieces of information, or if they simply did not respond at all. A subset of these students (20%) used VIVE headsets with built-in Tobii eye tracking sensors to track what they were looking at in the simulation, how quickly, how often, and for how long.

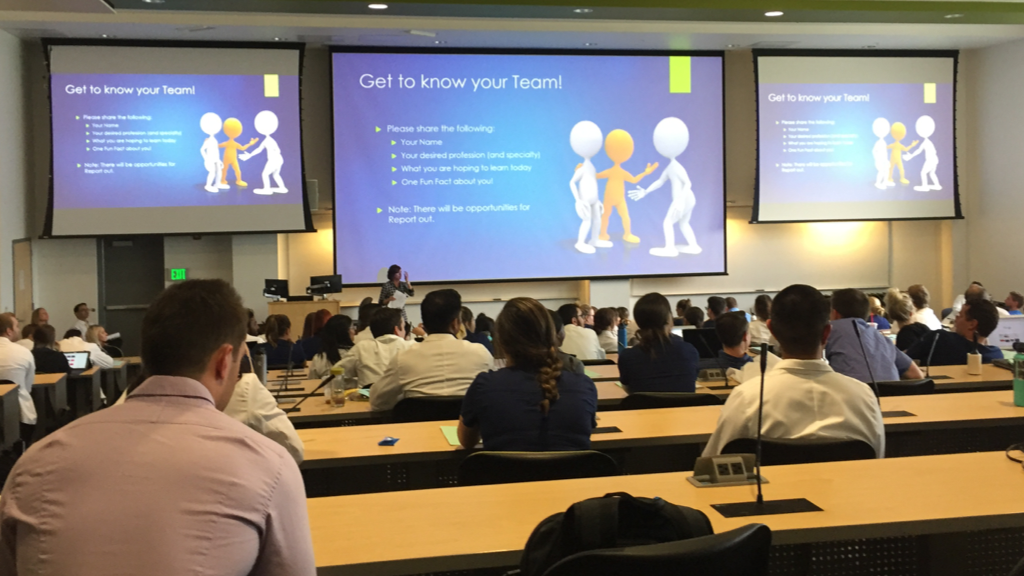

Figure 3. Medical and nursing students gather for their interprofessional communication training.

We then brought all 100+ students together for an interprofessional team communication training (TeamSTEPPS®), followed by another round in VIVE (their “post-test”) approximately one week later

What Did We Find, and Where is This Going?

After their training, students across the board increased the number of times they responded out loud to the simulation, with relatively few errors or missing pieces of information. Our initial analysis of those students using the eye tracking headsets shows some slight variation between pre-test and post-test.

At this point we can’t conclude whether this variation is beneficial or detrimental—more research needs to be done in this area. For instance, we can assess how experts perform in these simulations and compare their performance to student performance. Do the experts look at everything relatively equally, or are there certain elements within a particular setting that are more important to focus on? Taking advantage of the simulation and measurement capabilities of virtual reality technology will allow many questions in this line of work to be answered and will undoubtedly reveal many future opportunities for research.

Interesting in learning more about research at The University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine? Please visit: https://med.unr.edu/odi/research